- Jamaica Plain co-op tenants rejoice after judge’s order

By Brian Wright O’Connor

The allegations against the board president piled up over the years. Repair requests ignored. Phony court charges. Baseless eviction proceedings. Election rules violated. Surveillance. Harassment. Intimidation. Misuse of funds.

Residents of Stony Brook Gardens Cooperative in Jamaica Plain expressed deep relief earlier this month after a judge ordered the development’s embattled board leader Darlene Johnson removed as a director.

“I’m very happy because we’ll finally be able to have a little tranquility,” said a tearful Carmen Arroyo, who clashed with the board president after Johnson took over a handicapped parking space needed for her son, Daniel Arroyo Jr., who has spina bifida.

“To find out after 27 years that our handicapped parking space was gone – and she wasn’t even handicapped – was just wrong.”

Like several other tenants, Arroyo and her husband, Daniel Arroyo Sr., said they felt harassed after Johnson installed security cameras pointed at their doorway after they argued with Johnson.

For Massachusetts Superior Court Judge Rosemary Connolly, the last straw came a few weeks ago when she found Johnson continuing to stand in the way of a sweeping financial audit by Winn Management ordered by the court in late June.

Connolly, who appeared visibly frustrated by Johnson over the course of hearings on a lawsuit filed by Arroyo and other beleaguered tenants, cited the ex-board president’s “action and inactions causing delay and or hindering Winn’s prompt access to all the books and records required to be kept and maintained by the board under its by-laws.”

The 50-unit low-income housing development, squeezed in between Chestnut Street and Lamartine Street, was once considered a model co-op, home to mostly Spanish-speaking tenants and shareholders who gathered for cook-outs, celebrated family milestones together and depended on one another in times of need.

That all ended, they say, when Johnson joined the board in 2012 and quickly turned Stony Brook into her personal fiefdom – moving relatives into open units, playing favorites, failing to follow bookkeeping and election by-laws and using her position to terrify vulnerable tenants and allegedly enrich herself.

Symbolic of Johnson’s reign, they said, was her denial of access to a community meeting room, where residents often gathered, and padlocking a children’s play area in Stony Brook’s central courtyard. “She literally locked us out,” said Alfredo Liriano, the lead plaintiff in the lawsuit and one of the original residents of Stony Brook, which opened in 1993 as a beacon of affordable hope in a period of rapid gentrification.

After Liriano, a former Stony Brook board president who plans to run again, and a group of fellow residents filed legal action against Johnson and the board, the court ordered a long-overdue audit of the co-op books intended as the first step to bring Stony Brook into compliance with state and federal regulations governing low-income properties receiving public benefits.

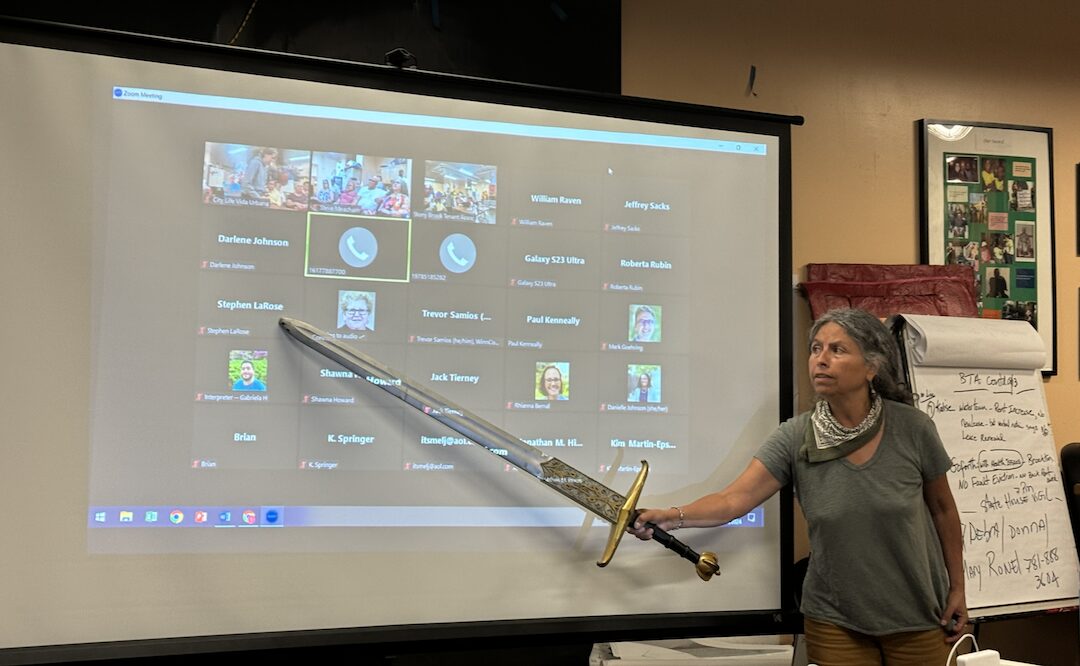

During hearings, the judge’s tough questioning of the previously untouchable Johnson prompted applause and whoops of glee among tenants watching the proceedings from zoom calls in the Amory Street offices of City Life/Vida Urbana.

Messages to Darlene Johnson asking her to respond were not returned. Her personal attorney declined to answer any questions, citing ongoing litigation.

John DeSimone, the attorney for the Stony Brook board of directors, said two other directors listed alongside Johnson in the lawsuit – Shawna Howard and Vanessa Lopez – are no longer board members and should be dismissed from the case.

“The people I’ve spoken to have all indicated that the board of directors – volunteers who have busy lives – have done the best they can,” said DeSimone.

Stony Brook residents who brought the suit have challenged the validity of recent board elections called by Johnson, saying she engaged in selective notification of tenants and failed to properly follow longstanding by-laws. They want Common Good, a non-profit property management company, to come in and run the development and a new board seated after proper elections can be held.

City Life, an activist non-profit that takes on housing and social justice battles on behalf of low-income households, has worked in concert with the City of Boston, Massachusetts officials, and a pro-bono team of attorneys from Nixon Peabody to pry open Stony Brook’s records and bring the co-op back into compliance and end the abuses tenants have allegedly suffered.

According to City Life community organizer Zafiro Patiño, the Stony Brook fight was so unusual in that it became so personal – even including accusations of racism against tenants by Johnson, an African-American woman initially trusted and voted to the board by residents with roots in Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic.

“The Latino people at Stony Brook voted for her at the very beginning. They trusted her,” said Patiño. “The problems began when she didn’t want to communicate with the residents and closed the door to them.”

During a criminal court hearing, Johnson accused Francisco Valdez, a native of Cuba who has lived at Stony Brook for over two decades, of assault and testified that he was racially biased against her.

The defendant scoffed at the accusation, pointing out that he was a Black Cuban. The judge dismissed the complaint after many delays in the case caused by Johnson’s failure to provide evidence, according to Valdez’s attorney.

“He is happy and content that Johnson is off the board,” said Marc Agramonte, Valdez’s partner. He said Johnson launched a vendetta against Valdez after he joined a dissident tenants’ group. The sham assault complaint was just another way to escalate the conflict and force them to move, added Agramonte. “She was not working in the interests of all the shareholders. Change is good,” he said of her removal.

Support for distressed Stony Brook residents began to coalesce after the September 2021 publication of an exhaustive investigation by El Mundo Boston. The story cataloged a record of unpaid vendors, undone repairs, a revolving door of managers and management companies, and a lack of transparency in where close to a million dollars in annual rents was going.

Johnson’s alleged practice of failing to cash rent checks and providing receipts was a strategy to facilitate evictions from the co-op, they said. Tenants also claimed that Johnson moved her daughter into one unit and a son, who is single, into a four-bedroom townhouse apartment.

They also accused her of mounting surveillance cameras outside the units of those who dared to challenge Johnson and said she completely controlled hand-picked board members who had little involvement in running the co-op.

When El Mundo Boston approached tenants listed as board members for comment, several cowered behind closed doors, refusing to discuss their involvement with the leadership group or explain why required annual elections hadn’t been held in nearly a decade and the cooperative had been dissolved as a corporation by the Secretary of State.

In the civil action, Judge Connolly on June 28 directed the Stony Brook board, then still headed by Johnson, to allow Winn Management Company to perform a comprehensive audit of Stony Brook’s books and ordered full cooperation by all parties.

When little to no progress was reported to the judge in subsequent hearings, Connolly lashed out at Johnson and the board, threatening contempt and expressing outrage that time had been wasted in Stony Brook issuing their own subpoenas rather than complying with the court order.

Rafael Pena, Stony Brook’s first tenant, said he was looking forward to the co-op going back “to the way it used to be – to have access to the community room, to celebrate together, to be part of a community together.”