Amidst celebrations, family fights for father’s vision for ‘Sports City’

By Brian Wright O’Connor

The crowd at Bushnell Park in downtown Hartford, Conn., is a long way from Puerto Rico but the music and aromas of the isle are everywhere.

Strolling along the fragrant food stalls with meringue booming from a nearby stage, Luis Roberto Clemente moves through the swaying celebrants like a telenovela star.

He can only take a few steps without being stopped for a handshake, a hug or a brief exchange of words with those who have memories and emotions to share about his father.

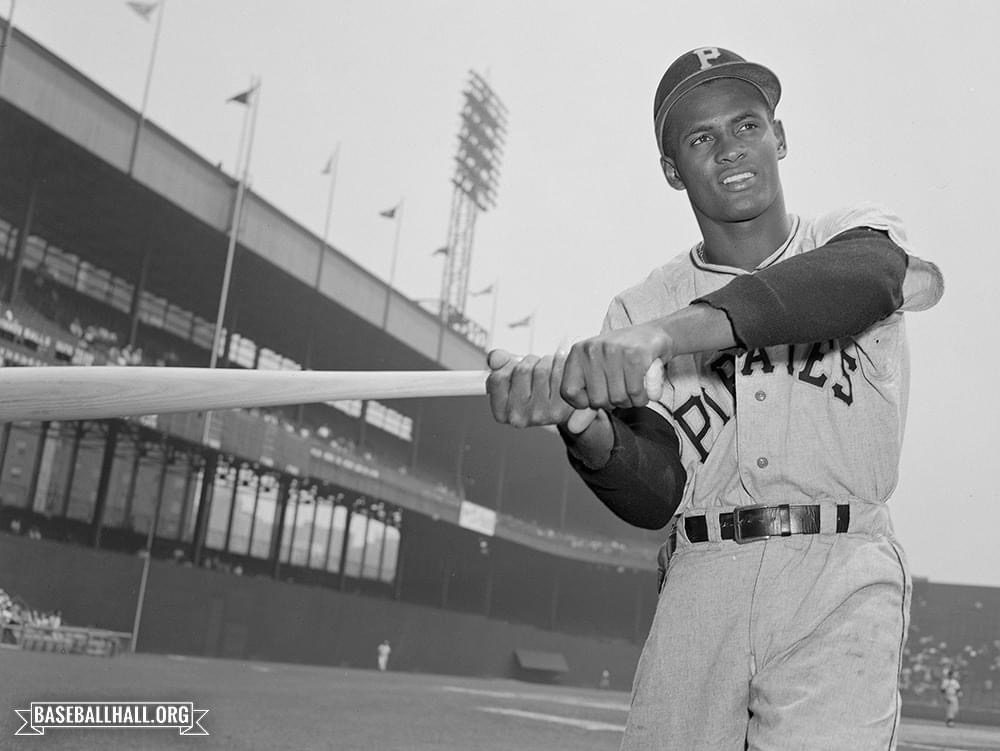

Everywhere you look, festival-goers are wearing tee shirts with the image of his father – the iconic baseball hero Roberto Clemente — on their back. Earlier in the day, his son waved at cheering spectators along the parade route to the shaded park.

The day before, Luis attended baseball clinics for boys and girls who love the game that brought fame and fortune to the kid from the cane-breaks of Carolina.

The clinics were hosted by the Double A team the Hartford Yard Goats, which was the first minor league ballclub to retire Clemente’s number 21 – chosen to represent the number of letters in his full name, Roberto Clemente Walker.

Later in the day, the Baldwin Bridge in Waterbury, Conn., was re-named in honor of the Pittsburgh Pirates legend. Meanwhile, resolutions praising the 12-time major league all star were passed by legislatures and city councils across the country. And this is just the start.

Hartford’s annual Puerto Rican Festival, always a highlight of summer in the Nutmeg State capital, this year kicked off a three-month commemoration of major milestones in the career of the two-time World Series champ.

“This year marks the 50th anniversary of his 3,000th major league hit as well as that fateful relief mission,” says “Luisito” of his late father, who died in a New Year’s Eve plane crash carrying supplies to earthquake-ravaged Nicaragua.

“This year is very, very special and we really appreciate the love that we get from the people here for my father and everything he meant as a baseball player and humanitarian.”

Clemente hit a double in his last at bat of the 1972 season, sending a line-drive into left field off Jon Matlack of the New York Mets at Three Rivers Stadium.

The swift right-fielder stood on second base, basking in the applause of the crowd as they honored his 3,000th hit, becoming only the 11th player in major league history to achieve that mark.

Only a few months later, Clemente was gone, killed in the crash of an overloaded Douglas DC-7 aircraft after the plane with a troubled mechanical history plunged into the Atlantic just off the coast of Isla Verde in Puerto Rico.

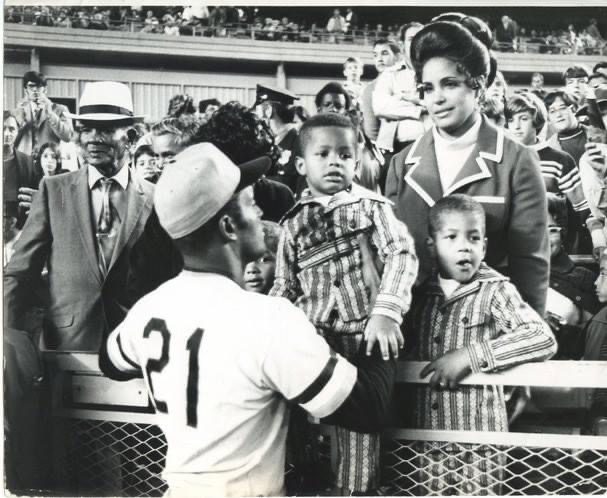

The baseball legend, who had premonitions of dying young and in a plane crash, was just 38. He left behind his wife Vera and three sons, Roberto Jr., Luis, and Roberto Enrique.

“My father had a great love for all of humanity,” says Luis, who was just 6 when his father kissed the family goodbye and set off for Managua.

“He especially cared for those who didn’t have a voice. He always stood up for the underdog. That’s why, 50 years after his death, people continue to honor and express their love for him.”

The handsome Pirate’s star with the rocket arm and humanitarian’s heart didn’t have to go to Nicaragua on that holiday flight, but he was concerned that the food and other supplies were being skimmed by corrupt military and government officials in Managua and weren’t reaching the people.

“That’s just who he was,” says Luis. “It didn’t matter to him where you were from, what language you spoke, the color of your skin. If he saw suffering, he was in your corner.”

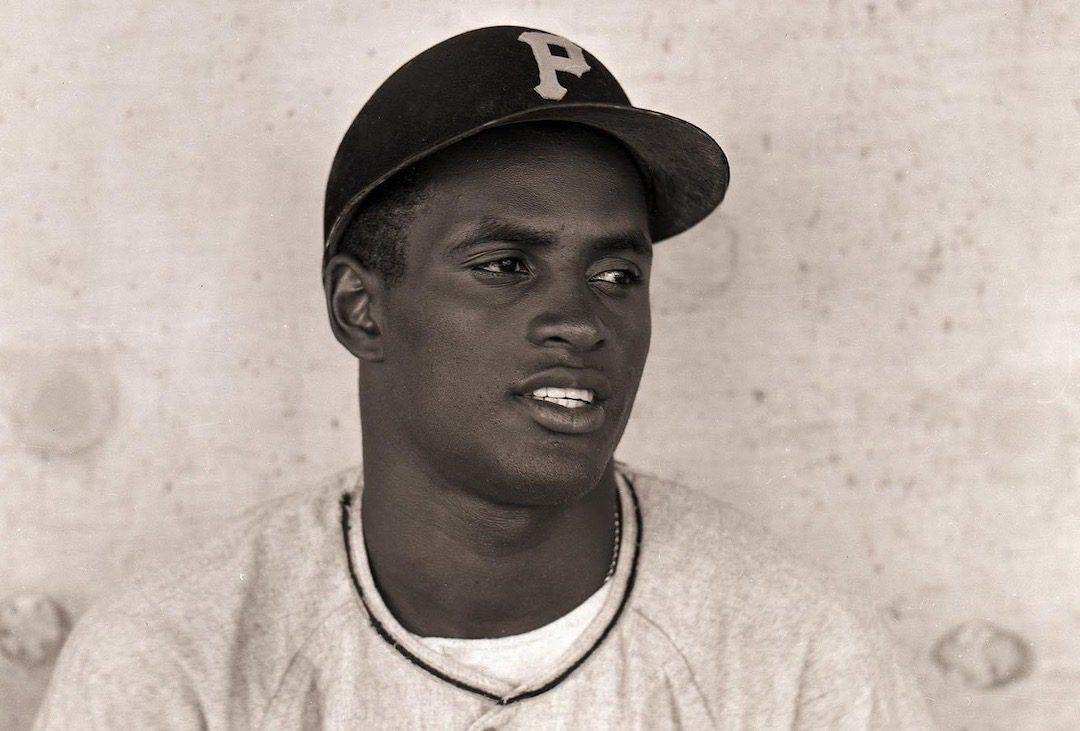

Growing up poor on the outskirts of San Juan, Clemente was a shy and deliberate child, who considered all he did with care.

His childhood nickname “Momen” was a shortened form of the word “momentito” because he often said that when others tried to pull him away from what he was pondering.

He came up in the big leagues when Jim Crow still ruled in the South and a Black Puerto Rican couldn’t sleep in the same hotels, eat at the same restaurants or socialize at the same country clubs as white players.

He deeply resented the segregated accommodations he encountered in Florida spring training camps and became an outspoken supporter of civil rights as protests built to a crescendo through the late 50s and 60s.

Years later, explaining his commitment, he told a journalist, “I said to myself: ‘I am the minority group. I am from the poor people. I represent the poor people. I represent the common people of America. So, I am going to be treated as a human being. I don’t want to be treated like a Puerto Rican, or a Black, or nothing like that. I want to be treated like any person that comes for a job.’ Every person who comes for a job, no matter what type of race or color he is, if he does the job he should be treated like whites.”

Clemente, who often choked up with tears when talking about granting basic human dignity to the poor and marginalized, extended his heart to children wherever he traveled. He sought them out, visiting sick kids in hospitals, often those who wrote him letters, without any press tagging along.

In honor of Clemente’s extraordinary dedication to charity, Major League Baseball re-named its annual award to the player who best embodies the spirit after Clemente.

The league will host a pre-game ceremony at Citi Field in New York this week to honor all the previous recipients of the Roberto Clemente Award. The Sept. 15 ceremony will take place before the Mets take on Clemente’s beloved Pittsburgh Pirates.

The Roberto Clemente Foundation, established by his family to carry on his legacy, will join with the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Major League Baseball Players Alumni Association, the Pittsburgh Pirates and the Clemente Museum to honor the Clemente Award recipients at a dinner in New York City.

The 50th anniversary of Clemente’s 3,000th hit will be commemorated by the Pittsburgh Pirates on Sept. 30 in the Steel City.

“He was there for the poor and those in need,” says Luis, “but also for his fellow players who weren’t making the big money and getting endorsements. He was a strong supporter of the players union. He stood up for everyone.”

Including his country, as a six-year member of the U.S. Marines.

In the decades since his tragic death, his family has done its best to carry on his legacy through the Roberto Clemente Foundation, providing, in the same understated way he did, hope and assistance to those living in the shadows of the most powerful economy on the planet.

In the midst of the celebrations this year, a legal wrangle over a sports complex intended by Clemente to serve the children of Puerto Rico has cast a shadow over the many events to mark the career of a man who was guided by a deep faith in God, love of family and country and a profound commitment to charity.

The Clemente family filed suit last month against the government, the governor and the House Speaker of Puerto Rico over their unauthorized use of Roberto Clemente’s name and image on license plates, for which drivers in the territory are being assessed a surcharge, to supposedly raise money for the refurbishment of Roberto Clemente Sports City in the baseball star’s hometown.

The 304-acre complex, conceived by Clemente himself a decade before his death, has become run-down, its ball fields, swimming pool, track and stadium slowly yielding to overgrowth and decay.

The family says the complex is a victim of deliberate neglect by the government as part of a scheme to take it over. The government claims that the sports park has been mismanaged by the non-profit running it, wasting taxpayers’ money.

Luis Clemente, president and chief executive officer of Sports City, Inc., points to numerous key abstentions by government officials on the board as evidence of efforts to stymie efforts to renovate and develop the complex so that it can become self-sustaining.

Disputes reached a head when the government passed a law to take back control of the land it donated in 1973 to fulfill Clemente’s dream of a place where kids could train to realize their own athletic ambitions.

“We have everything we need to be successful,” says Luis. “The government just has to be a partner, not an obstacle, so that the facility can be developed and used for its original intent. We have funding and a plan to bring it back after so much was lost during the pandemic. But we can’t move ahead as long as the government appointees on the board refuse to vote. They have an effective veto power on the future of Sports City.”

Luis’s words are suddenly drowned out by the pulsing beat of reggaeton from the speakers of a passing motorcycle. A passerby, walking by the seated Clemente, does a double-take.

“I loved your father,” he says. “I grew up watching him play. We all loved him.”

They embrace. Luis poses for a selfie. The commotion attracts others. Soon Luis is surrounded once more.

“The one characteristic about my father that stands out above all others,” he says before plunging back into the crowd, “is his respect for humanity. The respect for everyone. We grew up like a little United Nations, meeting people from all over the country, all over the world. He befriended everyone. That was so enriching for our lives to grow up and welcome everyone, not to look at humanity as separate races but as one people.”